Today, the economy is running as it did pre-Covid. There is even growth this 3rd quarter. Foreign workers are more often filling vacancies that would otherwise go unfilled. Greater flexibilisation leads to more and quicker changes of employees. Situations with staff from different language backgrounds and with different language skills are now more the rule than the exception, in just about all sectors.

However, language problems in the workplace go far beyond the obvious language barriers between employees with different mother tongues. On closer examination, up to 10% of all accidents at work turn out to be caused by language issues.

What opportunities do entrepreneurs and prevention advisors have here?

Marcinelle, a language accident?

Language accidents are already happening every day and are causing victims. This means that there is an opportunity here for prevention advisers. An opportunity to focus on it in the companies they work for or support. In addition, it is certainly necessary to put on the language goggles in the root cause analysis of occupational accidents.

According to Dutch research, some occupational groups run a greater risk than others: foreign-language workers and the more than twice as large group of low-literacy Dutch speakers together form a risk group of about 25 percent of the population. Various professions have a higher than average risk, such as drivers and production and warehouse workers.

Hidden language issues

1. Multilingualism prompts action

If you are already at a loss for words, then ask here

for the most useful applications for your company

2. Challenge under the radar: low literacy

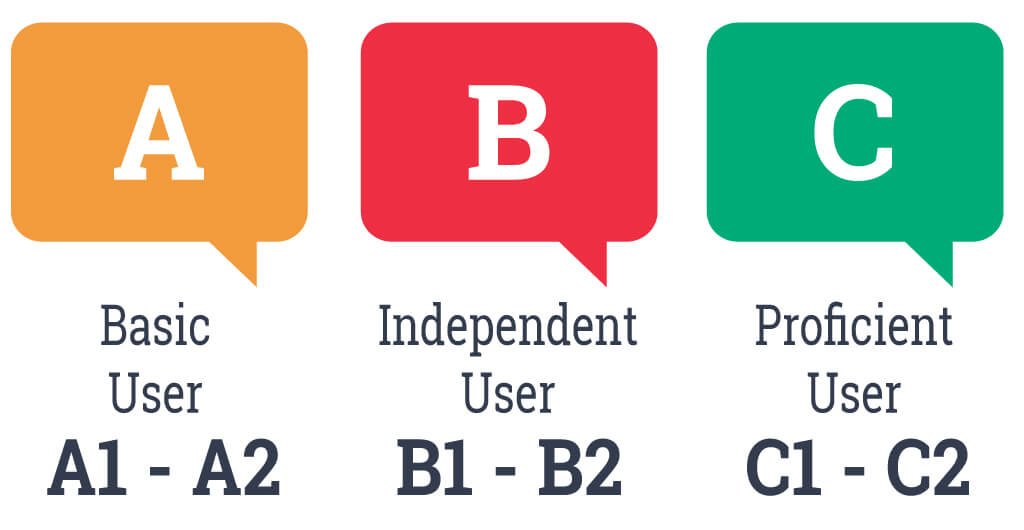

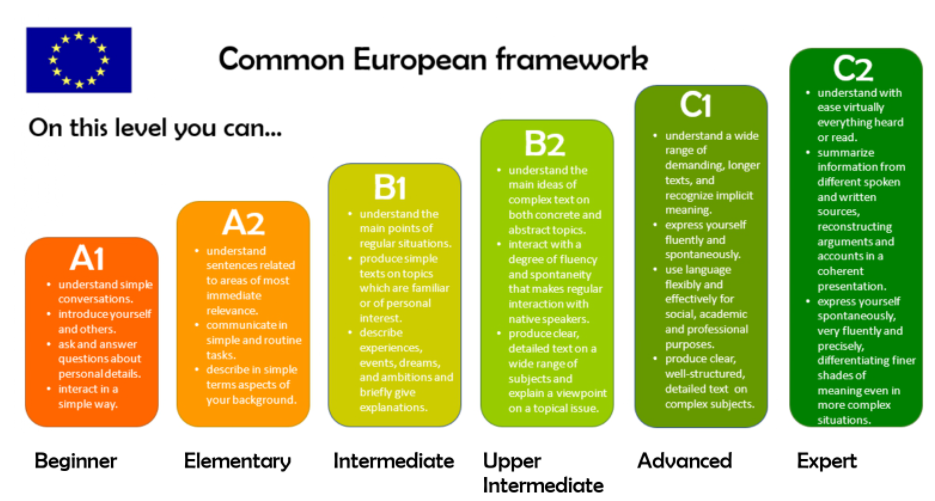

3. Language level too high: 50% of documents illegible

A photo or illustration is certainly helpful, but the correct language level of the text itself is decisive in understanding instructions. Perhaps it shows more "professional knowledge" for a prevention advisor to dare to deviate from jargon and, where necessary, to follow the employees' choice of words instead of juggling with words that are not used on the shop floor. At least offer them side by side.

In concrete terms, it is best to take this into account:

- write comprehensible texts at language level A2;

- measure the current language level of your texts;

- give the 'writers' in your company training in simple language use;

- use practical examples instead of more general theoretical descriptions;

- making texts more readable just by having a good graphic layout is not enough;

- drafting multilingual documents is not enough if you do not take into account the real language skills of your foreign-language audience;

- convert complex official manuals into simple instructions for use at language level A2.

More and more favourite subjects